History & Legacy

The Case Study House Program

In 1945, as World War II came to a close, Arts & Architecture magazine launched the Case Study House Program. Spearheaded by editor John Entenza, the program set out to tackle a looming challenge: how to build modern, affordable homes for the millions of Americans who would soon need them.

Click image image to view the original Case Study House Announcement

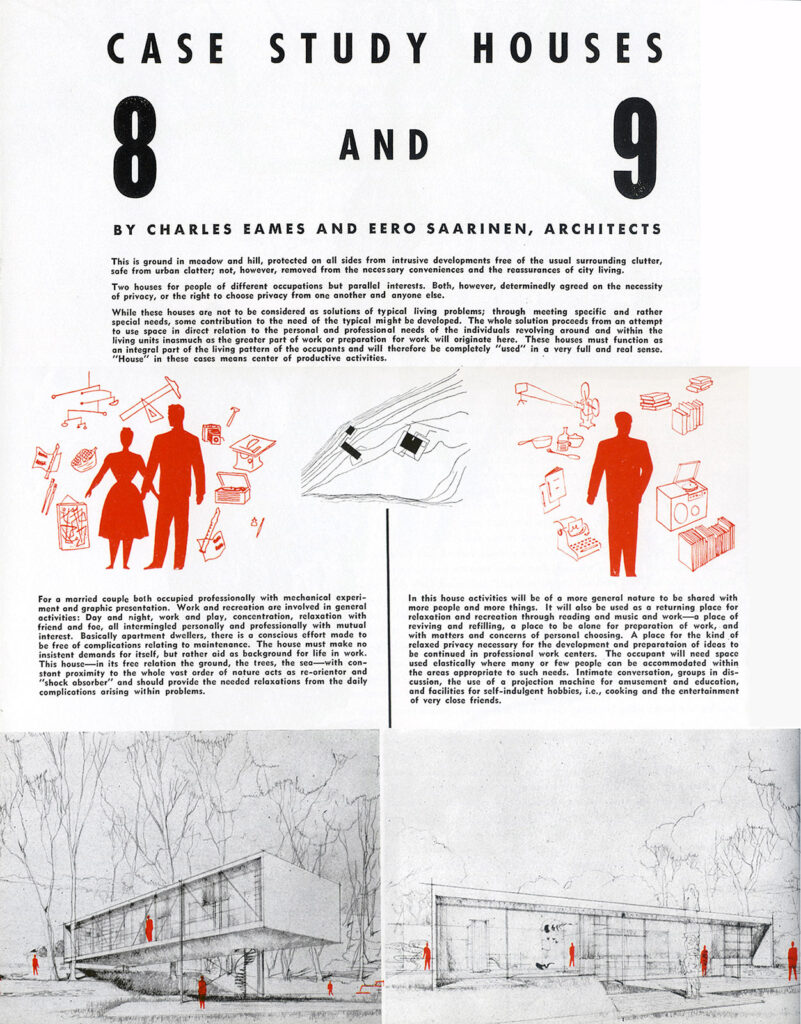

Click image image to view the original Case Study House #8 and #9 article.

Rather than compromise design for speed or cost, Entenza invited leading architects to envision houses that would be efficient, beautiful, and rooted in new materials and techniques developed during the war. These homes were built—or imagined—for real clients, reflecting the optimism and practicality of the era. The program went on to define a new chapter in modern residential architecture.

The Eames House

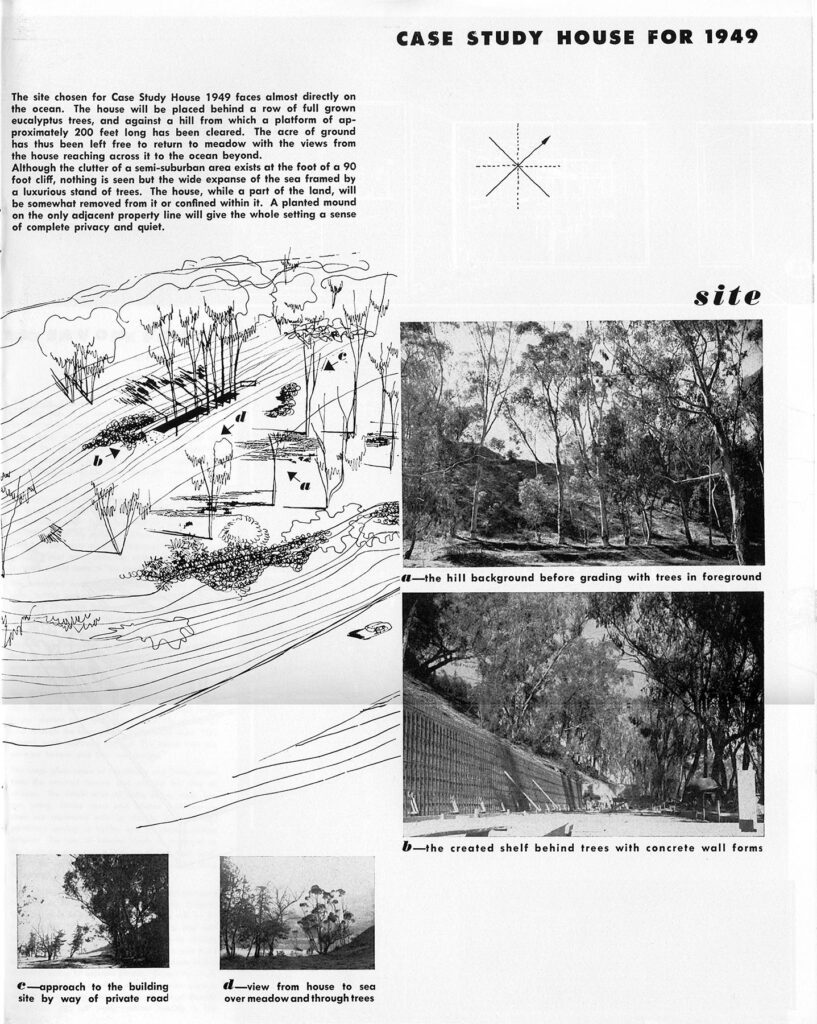

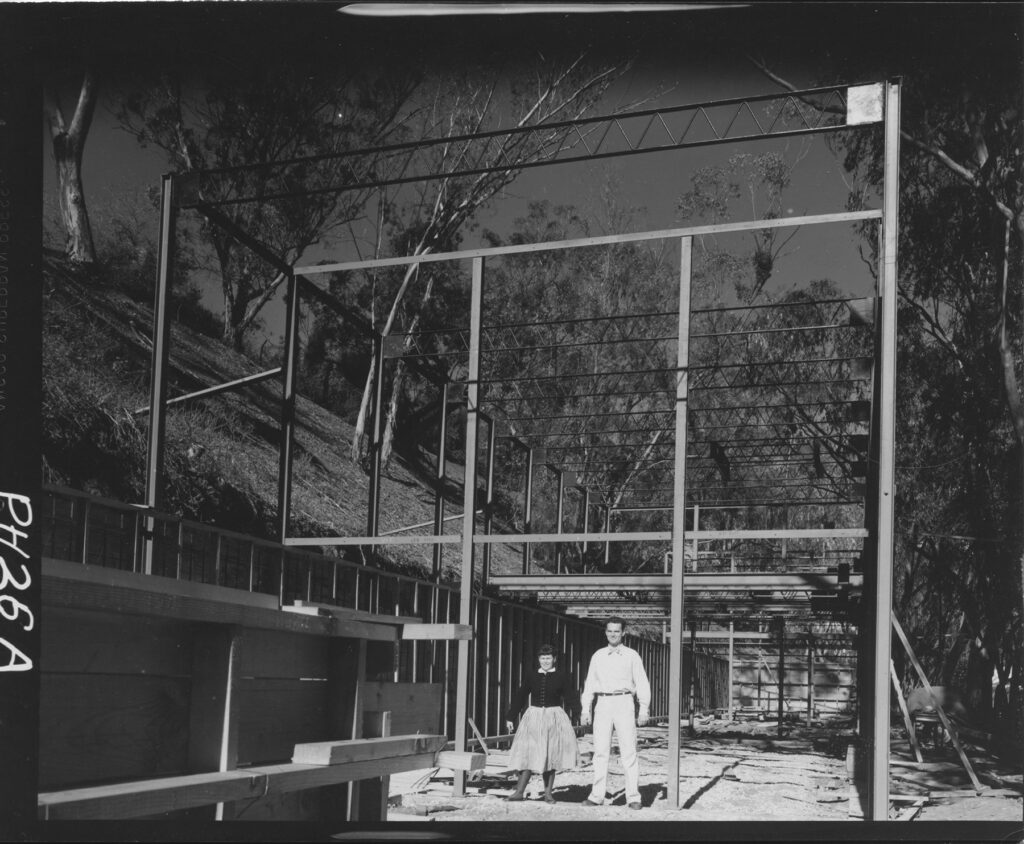

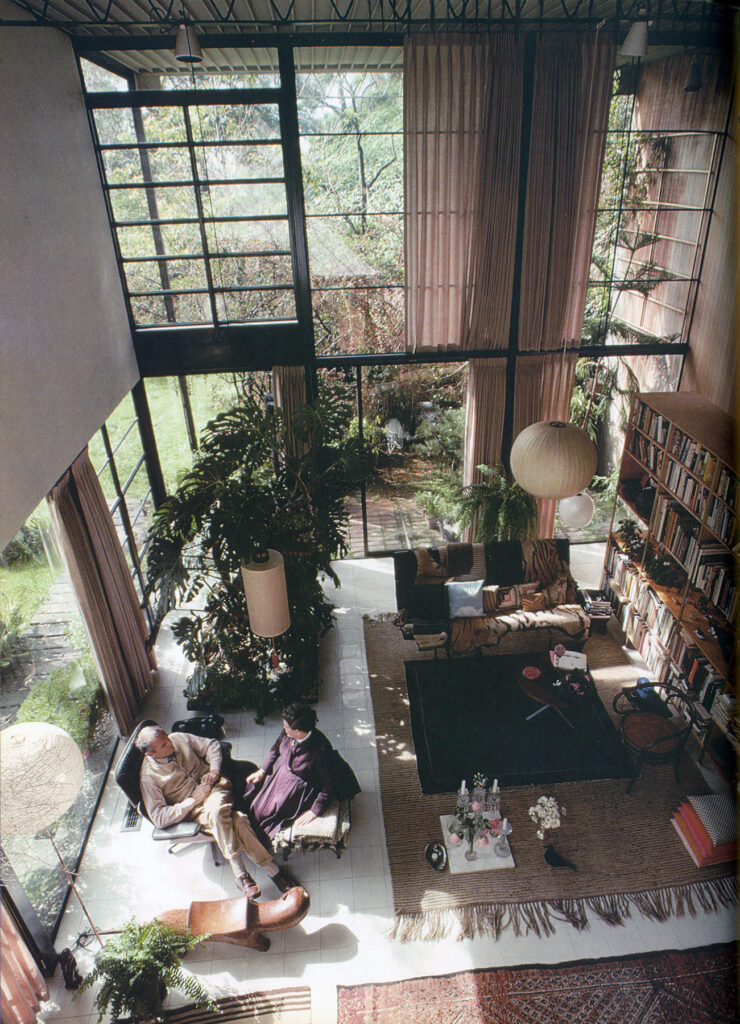

Charles and Ray Eames’ contribution to the program became one of its most iconic projects: Case Study House #8, better known as the Eames House. Designed in 1945 and completed in 1949, it served as both their home and studio in the Pacific Palisades, overlooking a meadow and the ocean beyond.

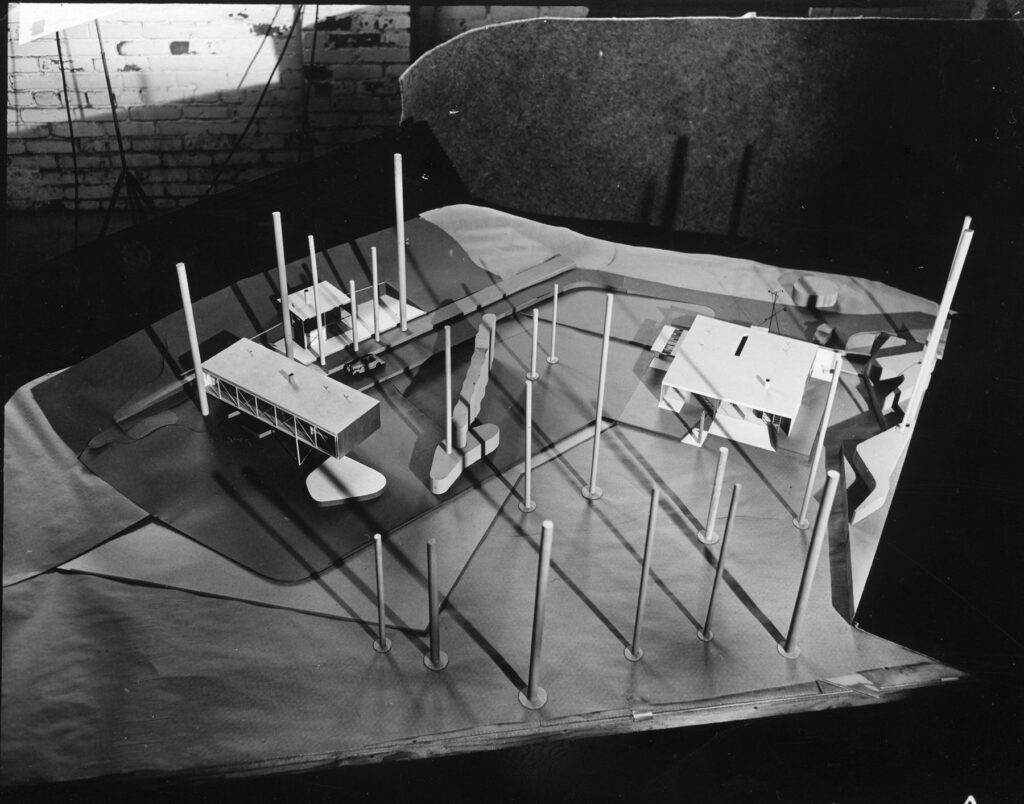

The "Bridge House" & Meadow

Their first design, the unbuilt “Bridge House” created with Eero Saarinen, was a steel-framed residence spanning across the meadow, cantilevered above the ground, with a smaller studio structure perpendicular to it. Due to materials shortages after the War, it would take nearly three years for the Eameses to receive the steel necessary to build. During that time, Charles and Ray picnicked in the meadow with family and friends, flew kites and did archery. By then, Charles and Ray had “fallen in love with the meadow,” in Ray’s words, and realized that they needed to avoid the “classic architect’s mistake:” destroying what made a site so special by imposing a structure on it.

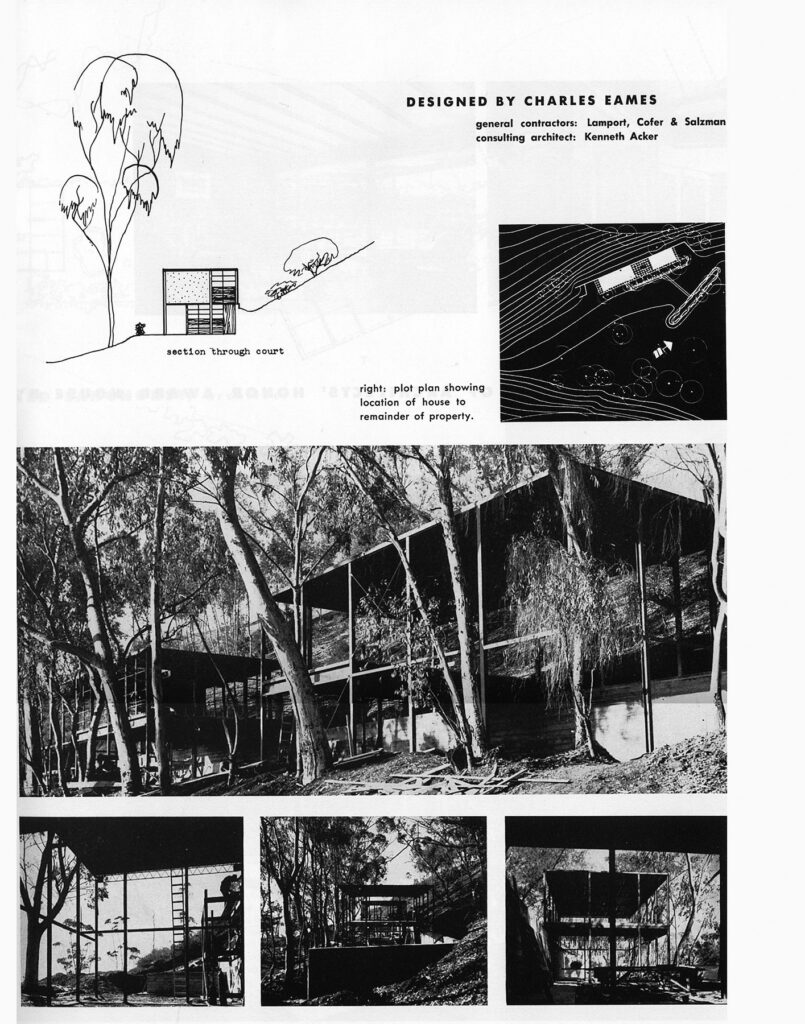

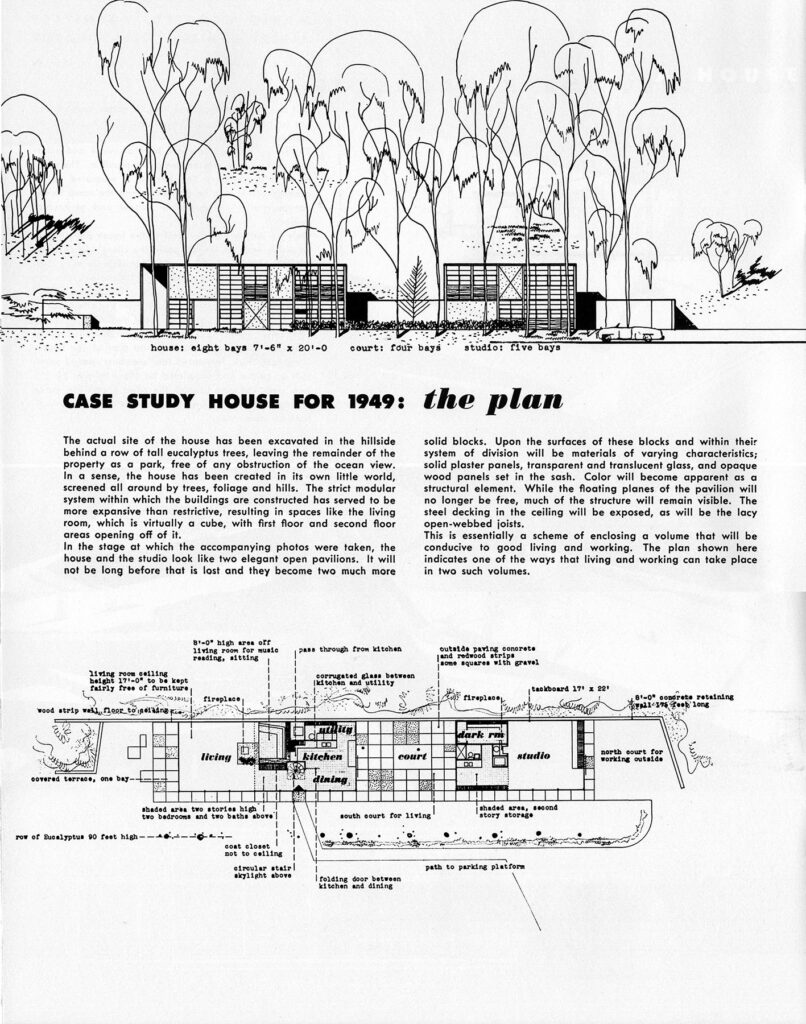

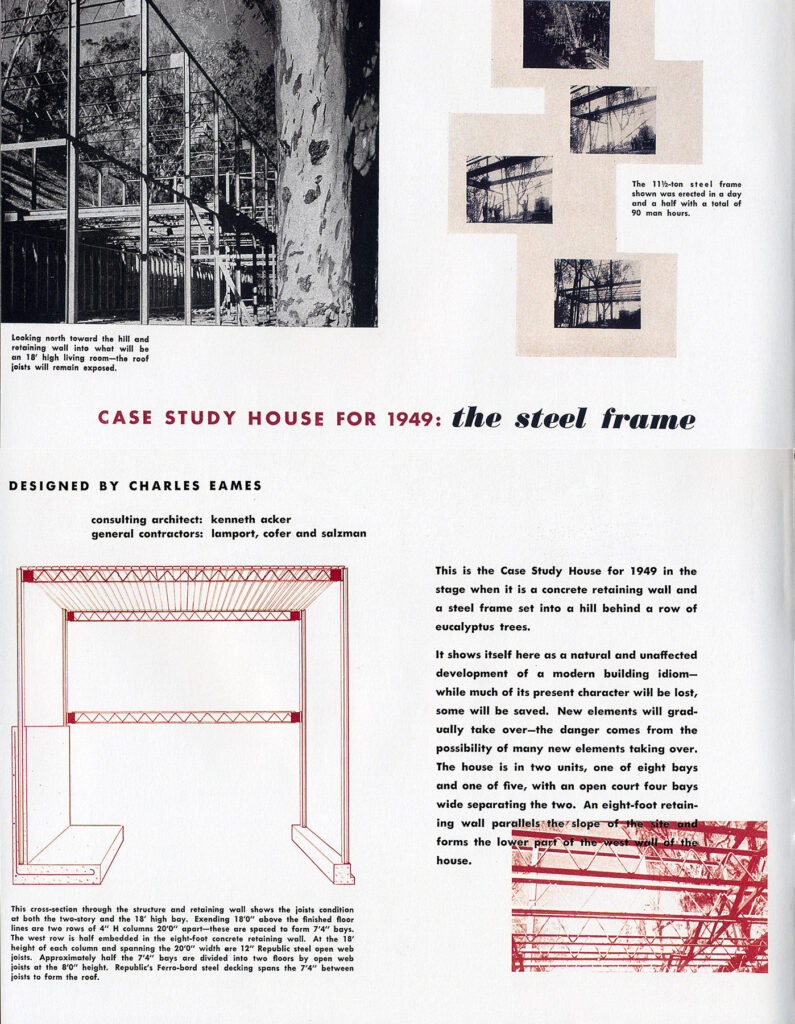

Maximizing Volume from Minimal Materials

Instead, Charles and Ray chose to redesign Case Study House #8 with two new guiding constraints. First, they sought to preserve the meadow and the line of nearly 70-year-old eucalyptus trees parallel to the hillside, and second, they wanted to “maximize volume from minimal materials.” Using the same off-the-shelf parts, but notably ordering one extra steel beam, Charles and Ray re-configured the design into what we know today as the Eames House. With both residence and studio tucked behind the trees into the hillside, the new design integrated the House into the landscape, rather than imposing the House on it.

The Meadow Today

The meadow, still in its natural, untouched state today, speaks to one of Charles and Ray’s most profound philosophies: that design should directly serve the act of living. The meadow became their outdoor living room, a space for picnics, gatherings, and work. By choosing preservation over domination, they demonstrated how modern architecture could harmonize with nature rather than conquer it. The meadow also exemplified their iterative design process, showing that patience and observation could yield solutions more profound than initial ambitions. It remains a testament to their belief that the best design emerges when you truly listen, to materials, to place, and to life itself.

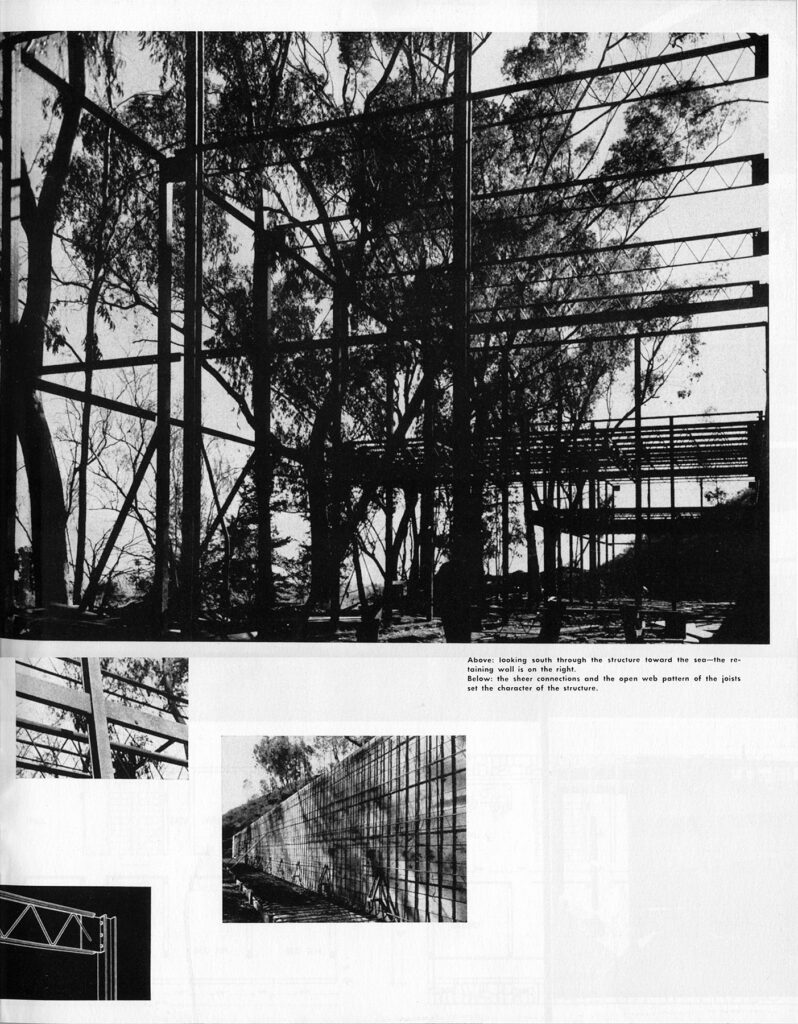

Construction Begins on The Eames House

Construction began in March, 1949, with the steel frames for both the Residence and Studio going up in just a day and half. When they weren’t working at the Eames Office in Venice, Charles and Ray oversaw and even contributed to much of the construction themselves—rabbeting prefabricated materials to join them together or putting on finishing touches such as the gold leaf just over the front door. The pair moved in on Christmas Eve, 1949, and lived at the Eames House for the rest of their lives—over the decades creating one of the most indelible design legacies in history.

The Studio

The Eames House Studio was Charles and Ray's creative workshop and the birthplace of some of the 20th century's most influential designs. Located just steps from their residence, this modest steel-and-glass structure served as a flexible space that would fit the need, however and whenever it presented itself. Whether that meant being set up as a workshop for experimentation or a film studio to work on films like Toccata for Toy Trains, the Eames House Studio embodies the breadth and character of Charles and Ray’s work.

The Studio was organized with characteristic Eames efficiency and delight, with every surface, shelf, and corner holding objects collected from travels, materials for ongoing projects, and prototypes in various stages of development. This “functional decoration,” as Charles and Ray called it, represented one of their core beliefs: that inspiration and good design hinge on curiosity and the willingness to draw connections between everything around us.

Further, the space itself—with its efficient layout, abundant natural light, and seamless connection to the outdoors—embodied their belief that the environment shapes the quality of work produced within it.

A Living Legacy

Unlike many modernist icons, the Eames House stands apart due to its warmth and texture—brimming with folk art, shells, toys, textiles, thousands of books, and objects gathered from travels. It reflects the Eameses’ belief that design should serve life, not overshadow it.

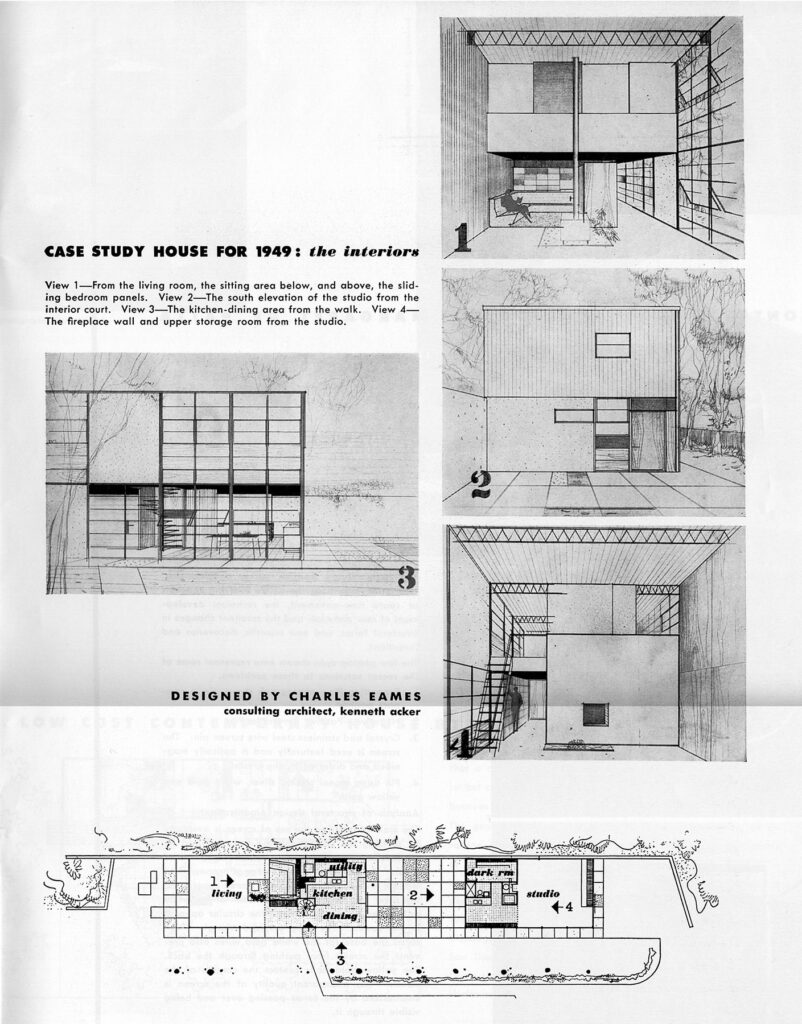

Today, the house remains almost exactly as it was during Charles and Ray’s lifetimes—a living laboratory of ideas and a lasting example of how thoughtful design can be at once modern, practical, and deeply human. As John Entenza once said, the Eames House “represented an attempt to state an idea rather than a fixed architectural pattern.”